Checking newly created WordPress accounts

In the WordPress database, there's an account called wp-config. That's clearly not a genuine user and looks like it was created maliciously.

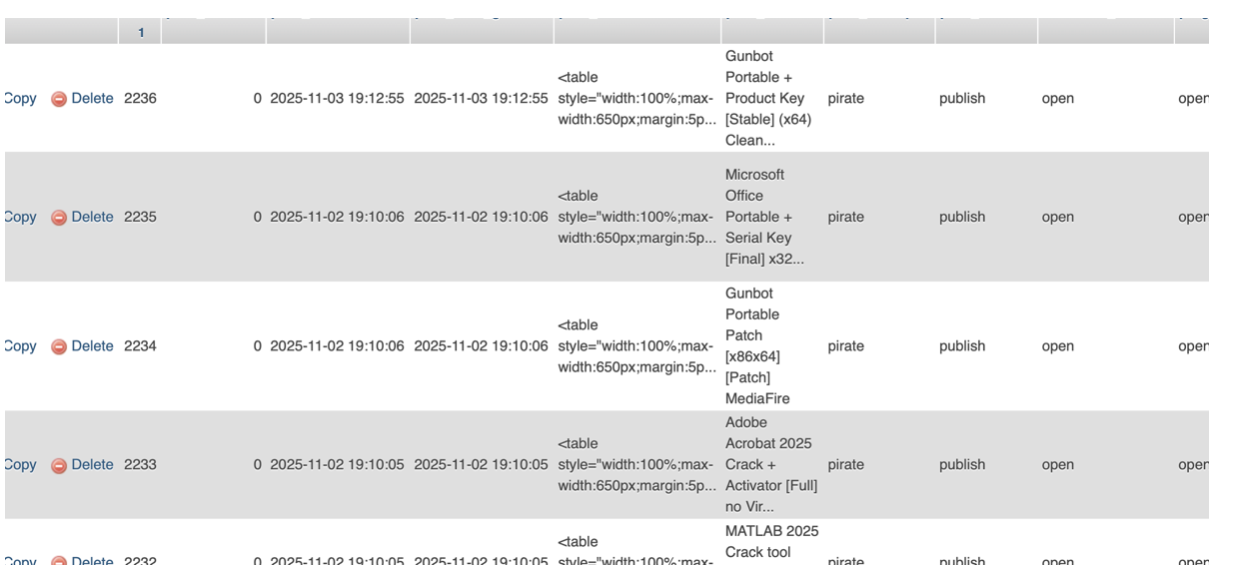

Checking what pages / posts were created

There are 341 pages in total, but the timeline doesn't add up. The first post is dated 2025-09-09 15:24:00, but the user account wasn't created until 2025-10-08 23:02:07.

Also, the posts are attributed to a user ID of 0, but there isn't actually a user with ID 0 in the database, which makes the whole thing even stranger.

Figuring out what happened

My plan was to use GPT-5.2 (OpenAI's latest model) to scan not just for the vulnerability, but also for any malicious code.

This is the prompt I gave GPT-5.2 (OpenAI's most capable model at the time):

This is a WordPress website that is already infected. There appears to be a vulnerability that allowed an attacker to upload malware, which is being used to:

- Create malicious posts

- Create unauthorised malicious user accounts

Please check the site for infected or compromised files and identify any malicious code or behaviour. Do not attempt to find or exploit the vulnerability yet, we'll do that later.

The model had access to a copy of the site files and could run commands / execute PHP inside a Docker container with no internet access. I expected it to take a couple of hours to properly iterate through everything.

Vulnerability found

The malware was found by the model after around 30 minutes. The source of it was an installed plugin called XWP-Captha, which claims to integrate with Google reCAPTCHA for human verification.

The plugin had malicious code embedded into it using another WordPress plugin called XSystem. XSystem itself appears to be legitimate software (often used by hosting providers to hide built-in plugins used for things like advertising, domain linking, reverse proxy management, etc.). In this case though, it was used to conceal the malicious behaviour inside XWP-Captha.

Here's the main overview GPT-5.2 gave me:

- Hides itself from the plugins list unless an attacker "marker" user-agent is used.

- Disables REST API + blocks XML-RPC post methods for normal users, but allows access with a secret query parameter (sec_key).

- Renames common cache plugins (e.g. wp-rocket → __wp-rocket) to break caching/security layers.

- "Locks" .htaccess and index.php by rewriting them back to base64-embedded "known good" content on every

init(persistence / anti-remediation). - Deletes any plugin folder containing ubh.php (a malware cleanup tool).

- Backdoor admin creation: creates user wp-config, grants administrator, then hides it from the user list (this matches the user I found earlier).

- Post creation routine: creates and publishes "pirate" posts (

post_excerpt = 'pirate') --- which lines up with the mass post creation we were seeing.

There was more, but those are the main behaviours.

Is the XWP-Captha plugin actually to blame?

I couldn't find much online about XWP-Captha (or XWP-Captcha, in case the name was misspelled).

I did find two links referenced in the plugin source code. The first points to https://www.webfactoryltd.com/, which looks like a legitimate company that sells WordPress plugins/services. The site doesn't mention this plugin at all, so it may have been included to make the plugin look more reputable.

From what I can tell, the core plugin code itself doesn't look malicious --- the problem seems to come from additional included scripts that are malicious. That suggests the plugin may have started out legitimate, and then been modified later to pull in a malicious code chain.

This line near the top of the plugin is what kicks the whole thing off:

require_once WP_CAPTCHA_CODE_DIR . '/wf-flyout/wf-flyout.php';

That appears to be the key addition that loads the next stage.

Why was this plugin on my client's website?

I just needed a plugin to handle human verification on form submissions --- but the bigger question is how I ended up installing a malicious copy in the first place.

The second link embedded in the plugin source pointed to a GitHub repository, but it now returns a 404. The Wayback Machine also has no snapshots of it. That could mean it was removed for hosting malware, was never public, or was private.

Most likely, I found it via that repo, saw the source code available, and assumed that meant it was safe. At this point, I can't confirm whether this was on me for not reviewing the code properly, or whether the repo originally looked legitimate and was later swapped/compromised.